Tulips: Mythic, Manic, and Viral (Why Flowers?)

Tulip mythology, tulip mania, a new paper that talks about tulip patterning, and plant pigments.

The tulip… an appropriate and timely bloom to illuminate, as I write this in early to mid May; the height of tulip season.

Red tulips

Cultivated in 10th century Persia, or modern day Iran. Mythology associated with the tulip in Iran and Turkey casts the tulip as a metaphor for perfect love out of martyrdom. Red tulips are “ (from Google AI Summary)…associated with the tale of Farhad and Shirin, two lovers whose tragic love story is said to have birthed the first tulip. The legend tells how Farhad, a stonemason, fell in love with Princess Shirin, but their romance was forbidden. In despair, Farhad took his own life, and Shirin followed, with red tulips growing from their pooled blood. This makes the tulip a symbol of perfect, passionate, and enduring love.”

I’ve had a love for tulips since I was a child. My parents saved an answering machine recording of me, begging them for permission to pick a red tulip that was growing in our yard. My parents said that if I were to pick the tulip, it would die. I didn’t want the tulip to die so I resisted the urge to pluck the vibrant bloom, and every day would visit it, marveling at its austere beauty. The dewey, smooth plains of vibrant color, the starbust center like the a cold flame, the insect like stamens; dusty, fluted oblongs on top of a delicate, crystalline stalks.

Tulip Mania

Perhaps you have heard of the phenomenon of “Tulip Mania” in the Netherlands. It’s often considered the first speculative bubble. Tulips became popular for their rich, saturated colors. In the 1630s, tulip bulbs sold at 10x the annual income of a skilled artisan. A single bulb would sell for 3,000 - 4,200 guilders, with an artisan making a mere 300 guilders annually. Shocking. Most prized among tulips were the Bizarden, yellow or white with candy-red stripes, flowing petals twisting and blazing.

A piece in the New York Times from 2017 “Broken Tulips: ‘That Last Gasp of Beauty Before Death’” recounts:

“…by 1636, a rare tulip with petals of red and white stripes that flowed out like ribbons of peppermint candy became so popular that for the price of a single bulb, a person could purchase eight pigs, four oxen, 12 sheep (all fat), 24 tons of wheat, twice that much rye, two hogsheads of wine, four barrels of beer, 4,000 pounds of butter, a quarter that much cheese, a silver drinking cup, a pack of clothes, a bed (including mattress and bedding) and a ship, according to a pamphlet from the time. Its name was Semper Augustus.”

That’s quite a shopping list. One tulip for 8 pigs, 4 oxen, 12 sheep, 24 tons of wheat, 48 tons of rye… it’s appalling to continue. I love flowers, but sheesh.

Scottish journalist Charles Mackay in his 1841 work Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds credits tulip mania for nearly destroying the Dutch economy. Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age, written in 2007 by Anne Goldgar (professor of early modern history at King’s College London) contradicts this narrative. A piece in Smithsonian Magazine by Lorraine Boissoneault, “There Never Was a Real Tulip Fever” states:

”In fact, “There weren’t that many people involved and the economic repercussions were pretty minor,” Goldgar says. “I couldn’t find anybody that went bankrupt. If there had been really a wholesale destruction of the economy as the myth suggests, that would’ve been a much harder thing to face.”

Tulip breaking virus

The Semper Augustus is now extinct, its beauty blazed out, a victim of the virus that caused its striking appearance. Only archival watercolors of it remain. Broken tulips are literally viral flowers; they can’t plant near other flowers, and it’s illegal to plant them in Netherlands without special provision.

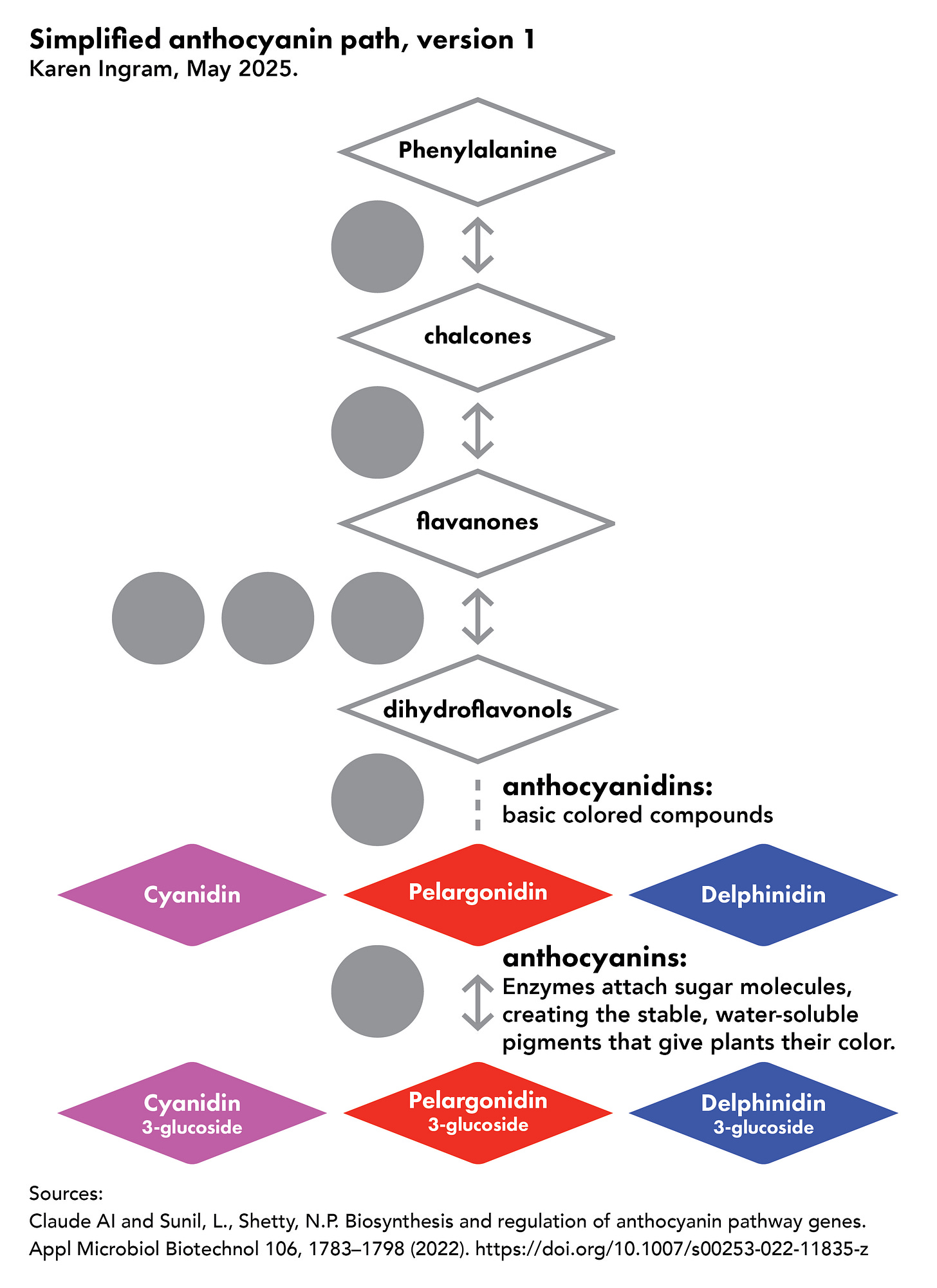

“How the tulip breaking virus creates striped tulips,” a paper published by three mathematicians in January 2025 in Nature has applied two math models to identify how the virus could have created the lively unpredictable stripes on the blooms by inhibiting pigment production from anthocyanins. Anthocyanins are antioxidant flavonoid compounds responsible for blue, purple, and red coloring in many flowers, fruits, and vegetables and even autumn leaves.

Tulip Math: Patterns and gradients

I’m not a mathematician, but I can still appreciate the thinking that goes into unpacking natural phenomena. According to these mathematicians, the virus inhibits anthocyanins through Turing patterns (this is a known term) and Wolpert gradients. I am applying the term “gradient” to Wolpert’s mechanisms here because I think it offers pictorial simplicity. From the paper, “The model… describes the viral inhibition of pigment expression (anthocyanins) and their interaction with viral reproduction, incorporates a pattern formation mechanism identified as an activator-substrate mechanism, similar to the well-known Turing instability, working together with Wolpert’s positional information mechanism.”

1. Turing patterns

Turing patterns are responsible for patterning you’d see on plants and animals like leopards and giraffes. From the paper: “Most Turing patterns are spots or hatches, but branching stripes can be another addition to the repertoire of mathematical art.”

2. Wolpert gradients

In Wolpert’s mechanism, according to the paper, “…cells retain positional information by sensing the concentration level [of anthocyanin] along a gradient.” Together, the mathematicians see a system that”… includes two famous pattern forming mechanisms, a Wolpert mechanism of pattern formation in spatial gradients, combined with a Turing instability mechanism.” This is all influenced by the tulip breaking virus.

Like I said, I’m not a mathematician, but this inspired me to go down a rabbit hole of tulip color expression.

Tulip chemistry, aka plant pigments: anthocyanin

A pigment is technically insoluble in water. Anthocyanin is a flavenoid, which means it is water soluble. Flavenoids In terms of paint, anthocyanin is like biological water color. Below is a simplified metabolic pathway I made influenced by tulip season and this paper. To create this image, I refeerenced Claude AI and another paper from 2022, Biosynthesis and regulation of anthocyanin pathway genes.

The anthocyanin pathway is regulated by:

Light (more sunlight often triggers more anthocyanin production)

Temperature (colder temperatures can increase production in some plants)

Nutrients available to the plant

Specific genes that control each step

This is why some plants develop more intense colors under certain conditions - like leaves turning red in fall or berry color deepening when exposed to more sun.

The beauty of broken

Occasionally my microbial paintings attract volunteers. The orange tulip above is an example. I’m letting it go, and will photograph it over time. We’ll see how my broken agar art turns out.

Tulips perfectly describe the human push and pull against nature; we admire them , we cultivate them, and we drench them in layers of metaphor.

Thanks for reading! As always, I welcome comments.

Why Flowers?

“Why flowers?” is a question I often get in relation to my artwork. Flowers are a frequent motif through which humans interface with nature. They are significant to us culturally, politically, scientifically. This piece part of a series, “Why Flowers?” in which I will share some context around why flowers are an inspiration in my work. Previous posts in the series are linked below.