"Design Nature"

A visit to Pratt institute: viewing failure as insight; calling on your known talents in unknown terrain; preservation, lifespans, and "volunteers".

This week I took a trip to Pratt Institute, to Jeanne Pfordresher’s “Designing Nature” studio course. Students in the course had been engaged in hands-on collaborations with living organisms including mycelium, algae and the microbial ecosystems that make up kombucha. They had been introduced to hydroponics, cute transgenic life and bio engineering, the question of scale, and many more intersecting topic areas in the realms of “practical solutions” AND “speculative solutions.” I joined them to share case studies from the evolution of my practice with a candid view into the experimental process. The students had many interesting questions and insights, and I’ll share below.

Insights to Novel Paths

To follow curiosity is to not default to what feels comfortable, and that comes with a good chance of unexpected results, or… failure. There is insight in failure, and that insight could lead you on a novel path. I’d like to share an example from my own experience. There is much to unpack here, but I will keep it brief*.

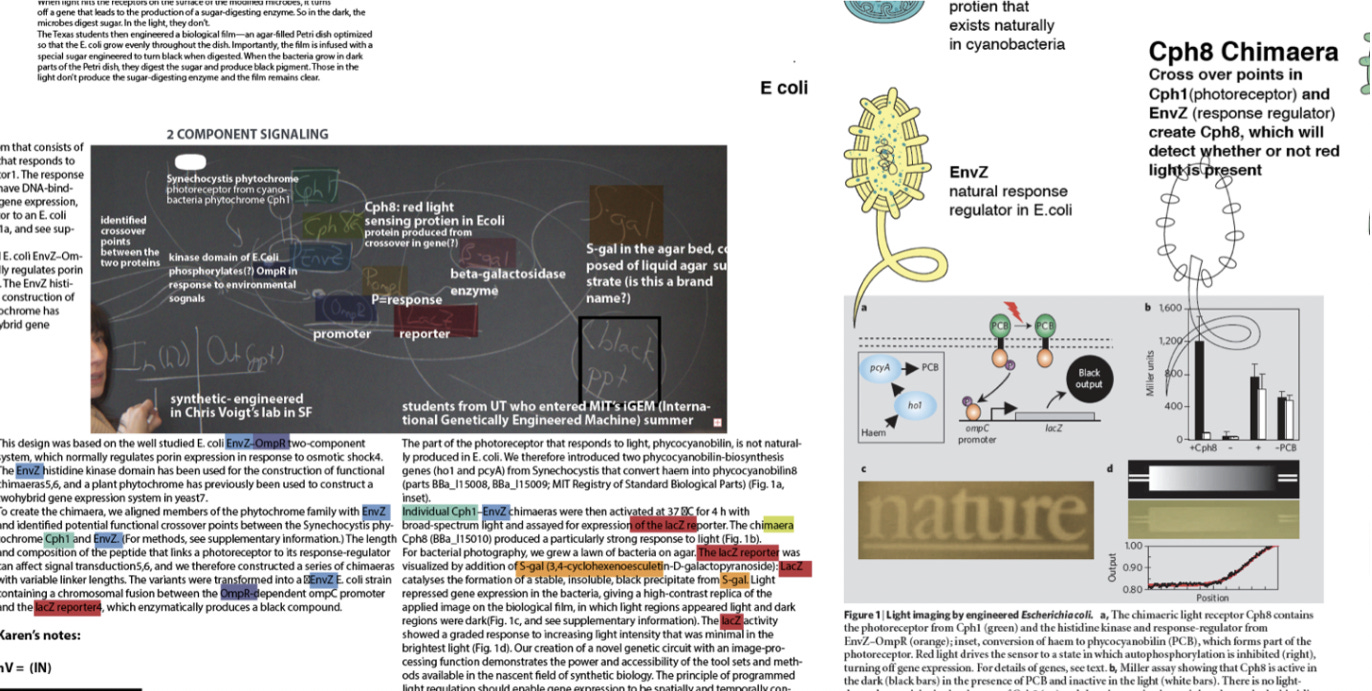

My first real foray into synthetic biology was an attempt at “bacterial photography” or “bactograph” at Natalie Kuldell’s class at MIT in 2013. Natalie is the Executive Director of the BioBuilder Foundation. I attended MIT as a visitor; I wanted to create an example of bacterial photography for an art show I was helping with. Unfortunately, my bactograph did not turn out, and I had no way of troubleshooting it. Somehow though, I found the whole process inspiring and was excited by the images created by others in the class.

I sought to make an “artifact” of the experience. It took me many many months, but I finally broke past the stagnation of a lack in expertise and made my artifact. It was simple; a one page diagram of the process and microbiology of the bacterial photography experiment. Sometimes things are very messy before they are simple.

Known Talents

So, how to break the stagnation of being a novice? Call upon your existing talents and skills. They’re there for you. It can be intimidating to dive into science, but artists and designers have their own set of skills they can use to process information. When I realized the scientific jargon was not something I was going to be able to understand without getting a PhD, I resorted to color coding. I color coded the terms and did my best to distill the role of each term, and where it fit in the process.

These days we are lucky to have new tools; it might be helpful to plop a scientific paper into an AI and get it distilled somewhat. I’m sure an endeavor like this would be made much quicker with the use of AI!

Because I followed curiosity and called upon my known talents, I ended up working with Natalie (and an amazing team including Katy Hart and Rachel Bernstein) on the BioBuilder textbook, and each lab chapter contains a similar diagram. I hadn’t even known the book was being planned.

Preservation and Growth Cycle

Back to photography; a question I get asked a lot, is how do I preserve my art. The answer, through photography, because I want to observe the lifespan of the Petri dish paintings. I could say more about why philosophically, and how technically, but for this post I’ll just share a brief example.

Lifespan

I seldom chronicle the full life cycle of a Petri dish painting, but here is one example. This is an anenome flower that was painted for a visit to NYU’s Sci-Inspire in 2022. The first photo is of the painting immediately after incubation (roughly 75 hours at 30°C), in October of 2022. The second is late November of 2022 after being sustained at 4°C. The colors have become much more vivid, particularly the orange, which has taken on a red hue and is much more vibrant that it immediately after incubation. The black is deeper, and the peach appears more pinkish, whereas before it was much closer to the orange. The third is several months later. The painting was kept at 4°C, but the water in the agar evaporated, leaving it with a pressed, dried flower appearance.

“Contamination” as Volunteer

This particular Petri dish painting didn’t make it to the bioabat show “in petri” ( ← replace for “in person”) because I realized it was contaminated before the show began. I was quite fond of this painting, so I included photos of it in the show and kept it for observation. Over the course of the next few months, I took several photos of this painting.

One student remarked they appreciated the fact that I continued to photograph the Iris as it continued to grow other microbes, mold and fungus. Another asked if I might deliberately expose my works to contamination (the answer is no) but to me, it hi-lights an artistic fascination with contamination. I’ve witnessed this enough of this artistic fascination to consider there might be a different word that could be used, rather than contaminant. I like “volunteer.”

Thank you to Jeanne for having me, the students for asking questions, and thank you for reading. Please feel free to comment below.

* You can read the longer version here: “Bacterial Photography: Creating Photosynthetic Images Using Living Microorganisms”.

Sorry to respond so late! I am ashamed to say I am late to Substack…but Karen I am so grateful that you visited my class. It was like they finally understood and had confidence to work with an organism. They could put everything they had learned to date, into context. Your work is beautiful, ephemeral and hands-on. They got it.

And, you also gave them confidence to read and dissect subjects they’re not so comfortable with. To slow down, to use their visual skills as a way into understanding difficult subjects.

You are amazing! And I owe you one! 😊

I really enjoyed the insights you’ve shared here. Early “failings” as learning opportunities, and new ways to view outcomes - both aimed for and unexpected. Such great views into the value of pursuing curiosity. Inspiring. And excited to keep reading more!